As Kevin Mattison pointed out a couple of weeks ago, it’s really tough to make a video game work as a movie, but we’ve been fortunate in the past several years to have some really great movies based on comic books. Based on a long personal history of comic book reading, and more than a little comic book movie watching, I’d like to offer some guidelines for future successful adaptations.

1. Don’t get caught up in the skin tight costumes

No.

Yes.

An exception, can be made for Jessica Alba. The Fantastic Four (2005) poster, after all, was far better than the movie itself.

2. Not too many characters

The third X-Men film, 2006’s X-men: The Last Stand, while continuing in the proud tradition of excellent costuming, is the perfect example of the “too many characters” syndrome. Most major comic book franchises date back to the 1960s if not before, and have hosts and hosts of secondary characters who have been introduced over the years. It’s a great temptation to cram in as many as possible, but given the limitations of screen time in even the most bloated 3-hour summer popcorn flick, too many characters make for a film that never really figures itself out. In X2 (2003), comic book readers get rewarded when the US military invades Xavier’s school for gifted youngsters, and several characters get brief but distintive cameos as the children either escape or are captured. X2, however, never forgets that it’s really about Rogue, Iceman, and Pyro, as they make their first adult choice to stand either with Xavier or Magneto. The Last Stand gives too many characters too many things to do, and it just gets lost quickly.

Also, films should generally pick one villain. I hate that the Batman films, starting with Batman Returns (1992), seem to feel that you absolutely need at least two major villains. This works acceptably well in Batman Returns, as Max Schrek is really the primary villain, leads to a scenery chewing contest in Batman Forever (1995), and just collapses in Batman and Robin (1997), which I normally like to pretend doesn’t exist. Similarly, after a solid Green-Goblin-centered Spider-Man (2002) and Alfred Molina’s wonderful performance as Doctor Octopus in Spider-Man 2 (2004), Spider-Man 3 (2007) features no less than three villains, and feels like two unfinished films stitched together into a rather shoddy whole.

3. Casting is critical (or, superhero movies are Shakespeare)

He also does spirit fingers.

Patrick Stewart, Ian McKellen, and Michael Chiklis are all good choices. They can all do big performances while retaining an emotional core. Quieter actors like George Clooney and Tobey Maguire generally are not. (Maguire gets away with Spider-Man, since Peter Parker is a nerd, but he never really feels right as the wisecracking web-slinger, and still can’t throw a convincing punch.)

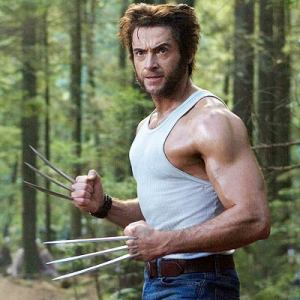

A good alternative source, apparently, is musical theatre, with its intense physical demands and requirement that an actor be able to do bombast with a straight face. Also, as Hugh Jackman proved, “jazz hands” translate well into “Wolverine claws.” Or rehab, for the same reasons, as in Iron Man‘s Robert Downey Jr.

4. When in doubt, make a good movie first

Finally, the source material is great, but when you have to choose between making a good movie and making a good comic book movie, always go for the former. I love The Dark Knight, but Christian Bale is actually a terrible Batman, and The Dark Knight isn’t really a great Batman movie. Batman Begins (2005) has its take on Batman right: he’s a ninja of sorts—sneaky, silent, and there are Batman comics where he does nothing but face off hand-to-hand against martial arts masters. Gadgets have also always been part of the Batman mythos, but The Dark Knight turns Batman into military special forces—not that smart, not really great at detective work, but good at punching. He’ll get in and get out to get his man, usually with an airplane. For all that, I love The Dark Knight, and I’m drooling over the upcoming sequel. Bale may suck, but Gordon, Dent, and the Joker are all great, and Nolan pulls them all together into a compelling world. I may not be convinced it’s Batman’s world, but I’ll hang out there as often as Nolan lets me.

Bonus #5. Remember that comic books are much more than superheroes

I know I said “finally” back on #4, but it has to be mentioned as a postscript that some of the best comic book movies are the ones you might not have realized started off as comic books, like A History of Violence (2005), The Road to Perdition (2002), and Ghost World (2001).

—

Gavin Craig is co-editor of The Idler. You can follow him on Twitter at @craiggav.

Filed under Uncategorized · Tagged with adaptations, comic books, comics, film, lists, superheroes

Comments

2 Responses to “Four rules for a successful superhero film”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...-

[…] I’ve argued before that while Nolan’s Batman films are wonderful, they don’t really have a handle on Batman himself. Nolan “turns Batman into military special forces — not that smart, not really great at detecti… […]

Have to agree with you regarding these rules :-)