How Robert Altman helped me justify being lazy in film school – Pt. 1

There was a solid stretch of time during my early goings in film school where I thought that I might be in some trouble. I worried about my disinterest in traditional screenplays or, more to the point, the screenplay itself. That is not as to say that I didn’t and don’t appreciate them (I read The Social Network’s script twice), I simply didn’t and don’t have the attention span for them, generally speaking. I was only interested in the translation of moments and images from my head to the screen. If only it were so simple.

As it stands I still rush through scripts, both when reading and writing. Why can’t a cast and crew just translate what appears to be incoherent, occasionally serial killer-esque scrawlings in a notebook? Why doesn’t it make a difference when I assure them that “I’ve got this”? Why can’t everyone just be brilliant so that I don’t have to worry?

As is my nature, instead of accepting that I am doing things the wrong way and adapting, I began seeking justification for my approach. My tireless efforts to find a kindred spirit were rewarded when a filmmaker I was obsessed with at the time, Paul Thomas Anderson, led me to a filmmaker he had been obsessed with all his young life: Robert Altman. He had cited Altman as a major influence on his film, Magnolia (1999), a sprawling, multi-character melodrama that had blown me away (still does) and insisted upon multiple viewings (no small feat for a three-hour film about cancer). I immediately snagged a copy of Short Cuts (1993), which, being a sprawling, multi-character melodrama itself, seemed like as good a place to start as any. It didn’t hurt that it was based on multiple short stories by Raymond Carver, whom I love.

Altman’s influence on Magnolia was immediately apparent, particularly in the camera work, which glided, pushed in and zoomed like it was trying to take in everything while simultaneously maintaining focus on its protagonists. The similarities between Short Cuts and Magnolia gave me an access point, but there was something about Altman’s film, something I hadn’t come across in all my years of cinematic bingeing. I immediately hit imdb.com, jotted down every film Altman had ever made or been involved with and went to work. I read interviews. I watched behind the scenes footage. This guy had some pretty radical ideas. He cared little for screenplays, even his own. They were just an excuse to set up a camera.

That’s not as to say that he didn’t use them, it’s just that he really only needed to read them once, you know, so he knows what the movie’s about, then he was off and running. Often times he would show up on set and ask what scene they were shooting that day. He has said that screenplays were just a means by which he could remember all of the character’s names. The truth is, regardless of his approach, he loved a good story. He loved a good character even more.

The second Altman film I saw was full of characters. M*A*S*H (1970) was, in fact, all character and next to no story. Most of us know these names by now: “Hawkeye” Pierce, Trapper John, Major Frank Burns and “Hot Lips” Houlihan. Stationed in an M*A*S*H unit in Korea (Altman insists that it’s actually Vietnam. The studio made him change it), these characters pass their time with pranks, shenanigans and “friendly” games of football, all the while dealing with the surrounding (Vietnam) war and the atrocities that come with it. It is the darkest of dark comedies, the kind of film that usually has a hard time getting made. Altman himself has said that it probably wouldn’t have had the studio not been distracted by numerous other projects sure to garner more profit. He was pretty much left to his own devices, which resulted in a Best Picture and Best Director Oscar nomination. It won for Best Screenplay, which is funny because the screenplay is actually quite dull and, ironically, not very funny. It’s a good thing that he cares little for them.

It's actually kind of charming, in its own way

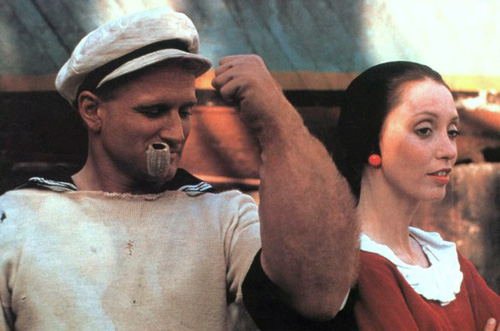

As I delved further into Altman’s filmography I found that he was no stranger to genre-bending, subversive and, occasionally strange projects. Brewster McCloud (1970), for example, is about a boy who lives in a fall out shelter and dreams of being able to fly. It’s a strange one, to be sure, but it actually works in its own way. Some of them didn’t. A Perfect Couple (1979) is a film brimming with good ideas that don’t make sense in conjunction with one another, and the post-apocalyptic, sci-fi “thriller,” Quintet (1979) is nearly unwatchable. Pret-a-Porter (1994) holds little interest to those with even less interest in the fashion industry. You’ll notice that I didn’t mention what is widely considered to be one of Altman’s biggest flops, Popeye (1980). That’s because I like it. Deal with it.

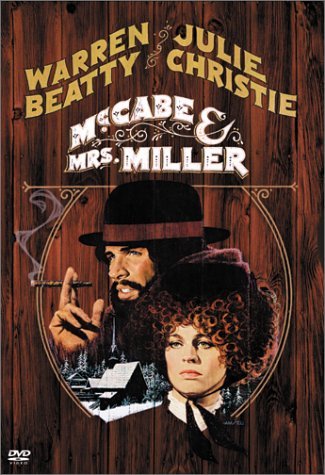

Nobody’s perfect, but when he hits the ball squarely he knocks it out of the park. I had a string of good luck with the next few films, all made in what I consider to be the best decade for cinema: the ‘70’s (We’ll ignore ’79, the year Altman stumbled, then tried to regain his footing for nearly a decade). McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) is a brilliant, subtle anti-western fueled by the melancholy music of Leonard Cohen. Its story is simple: A mysterious man with a past rides into an upstart town and teams up with a prostitute to run a successful brothel. The characters are familiar. What isn’t familiar, as usual, is Altman’s approach. His gunslinger may be more lucky than skilled and the films big shoot out is quite unorthodox. Could you imagine John Wayne sneaking up behind someone and shooting them in the back? The final moments are at once brilliant and tragic.

Nobody’s perfect, but when he hits the ball squarely he knocks it out of the park. I had a string of good luck with the next few films, all made in what I consider to be the best decade for cinema: the ‘70’s (We’ll ignore ’79, the year Altman stumbled, then tried to regain his footing for nearly a decade). McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) is a brilliant, subtle anti-western fueled by the melancholy music of Leonard Cohen. Its story is simple: A mysterious man with a past rides into an upstart town and teams up with a prostitute to run a successful brothel. The characters are familiar. What isn’t familiar, as usual, is Altman’s approach. His gunslinger may be more lucky than skilled and the films big shoot out is quite unorthodox. Could you imagine John Wayne sneaking up behind someone and shooting them in the back? The final moments are at once brilliant and tragic.

I followed that one up with California Split (1974), which featured the brilliant Elliott Gould and George Segal (Yep, the boss from Just Shoot Me. Remember that show? Of course you don’t) as a couple of gambling addicts destined for the big let down. It’s little known, but I believe it to be one of Altman’s best. There’s even more Elliot Gould gold (see that?!) in The Long Goodbye (1973), in which Altman turns the private eye genre (and the character of Phillip Marlowe) on its ear. His decision to translate the Marlowe character’s noir, inner dialogue into inane, outward babbling is inspired and Gould pulls it off perfectly. Another favorite.

I capped it off with the film many consider to be his masterpiece: Nashville (1975). Like M*A*S*H, Nashville is a film about people, not plot. It is also a film about time and place, with Altman’s pioneering use of layered dialog creating a palpable energy that firmly places you within the its world. There is always something happening, even when nothing is happening, and he insists that you pay attention. Altman was on a roll.

Many believe that roll halted after that Popeye debacle I mentioned earlier, and the ‘80’s saw him delving into more personal, smaller films. He looked to theatre, adapting stage plays like Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982), Streamers (1983), Secret Honor (1984), Fool for Love (1985) and Beyond Therapy (1987), to varying degrees of success. He did occasionally try to hit a mainstream target, but often missed ala’ the aforementioned Popeye and the awkward and disposable teen flick, O.C. and Stiggs (1985). For my money, Popeye, Fool for Love and Secret Honor are all pretty great, even if the box office didn’t agree.

His renaissance came in the form of The Player (1990), which skewered Hollywood in expert fashion and featured multiple stars playing caricatures of themselves. The opening shot is brilliantly staged and lasts for over seven minutes. I doubled back after The Player and viewed A Wedding (1978), about an upper class family wedding gone awry. It’s another underrated Altman film, featuring multiple characters and layered dialog. It was clear to me at this point that his films were changing the way I viewed and approached the medium.