Walking the bounds

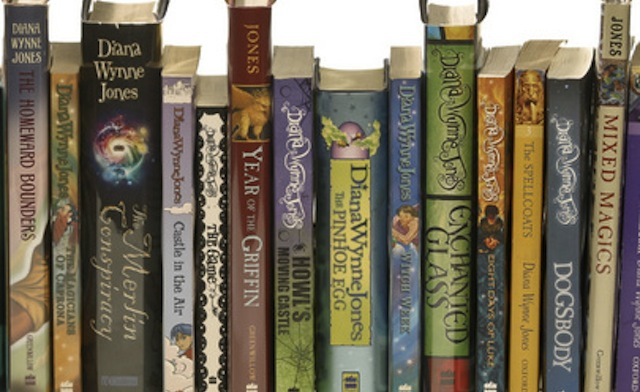

Diana Wynne Jones

One of Jones’ books always eluded me. I found it once at a library but never saw a copy again. As I grew older I was haunted by images from the book — a skeletal ship, a man chained to a rock, a girl with a withered arm — and, having forgot the title, began think that I’d dreamed it rather than read it. It was The Homeward Bounders.

The Homeward Bounders is a book about not finding home. Jamie narrates the story; he is twelve and is speaking into a machine left behind by Them. (They are always in italics.) Jamie grows up in late 19th century London, the son of a grocer, exploring the city and getting into trouble. He stumbles upon Them playing a wargame, and, after consulting the rules, they decide, rather than killing him, to throw him onto the bounds.

The Homeward Bounders is a book about not finding home. Jamie narrates the story; he is twelve and is speaking into a machine left behind by Them. (They are always in italics.) Jamie grows up in late 19th century London, the son of a grocer, exploring the city and getting into trouble. He stumbles upon Them playing a wargame, and, after consulting the rules, they decide, rather than killing him, to throw him onto the bounds.

This is the heart of the book, even though it’s only about 50 pages. Jamie ends up first in a world with nomadic herders, and many others that blur together for him as they do for us. He stays until the bounds call him, which they do sooner or later, and send him somewhere else. He is a Homeward Bounder — the rules are that if he ends up back at Home, he can stay. Other rules — he can’t die. It’s lonely. It doesn’t end.

Luckily, Jamie comes to a boundary that drops him into the sea. He is picked up the Flying Dutchman — his ship has got rid of anchors, to show that they have no hope — and dropped on an island where he meets a man in chains (who we know must be Prometheus, but Jamie doesn’t). Jamie finally meets other Homeward Bounders (a young woman exiled from her own world and a demonhunter), finally makes plans to defeat Them, and finally loses hope.

Diana Wynne Jones’ books are often madcap and hilarious, but not this one. There is humor, but the real triumph of the book is a flawless evocation of some of the bleaker moods: loneliness, hopelessness, dark irony, the feeling of being home everywhere and nowhere. I trust Jones, and I trust that any story she tells me will be important. Until I picked up The Homeward Bounders, I didn’t know I needed to read a story about how a boy can become an anchor.

—

Suzanne Fischer is a historian and writer who lives in Detroit. She cares about people, places, and things. Find her on Twitter as @publichistorian