Unpacking loss, unpacking Nox

You can’t know grief until you experience grief. Its pain is ineffable. It socks your body and mind and ruins all sense of reason, meaning. Anything you’ve believed or held true becomes subject to question when someone you care for passes away because something impossibly ridiculous has happened — a living breathing someone gives up the spark of life and enters a world of objects. Voice, heart, soul, mind, touch. . . all removed from personhood. Unmagicked into a thing, a someone becomes corpse, becomes ash, becomes not. As death and grief are universals that rip at the fabric of human understanding, of course this subject matter has inspired much in the way of the arts. Though I’ve been moved by many a film and story, I reserve this space to discuss a text that maybe you won’t happen upon on the bestsellers case at your bookstore, or hear about from a friend. Anne Carson’s book/assemblage Nox (2010) has affected me deeply as it so closely and strangely performs and researches the reaches of grief through its remarkable structure, art, truth and tone. This odd text is worth seeking, finding, discovering and revisiting again and again.

Carson lost her brother twice. A kind of shade in life, he lived apart from his family. Estranged for long periods of time, he kept little contact with his sister. He’d pass along snippets of information by post — his envelopes acting as clues to his whereabouts overseas. He was a brother, blood, but he existed and didn’t. His death gave his absence a new permanence and the author was left with the odd practice of learning to grieve for a shade — giving up he who was already a ghost. Nox could be interpreted as her attempt of reconfiguring him, erecting a monument, seeking her brother, seeking peace. In making her piece, Carson creates a solid, material presence in the face of loss. It commemorates, elegizes, and yearns for him. Both heartrending and comforting, the text exposes her wounds, but also creates a space for commiseration through the making-public, the opening out of her pain to a world of others floating in the same limbo of emotions.

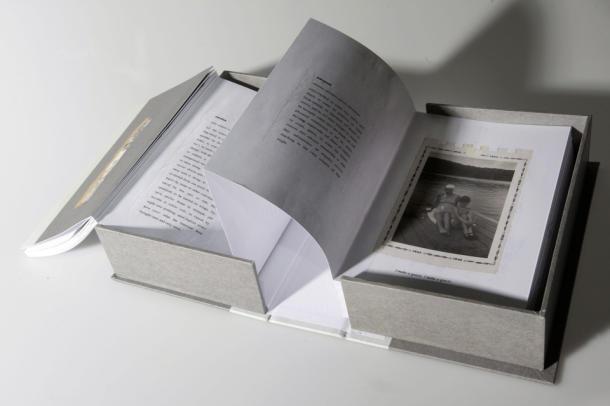

Paradoxically apt then, Nox is a book that is not one. A grey hardcover case, something like a pencil or cigar box, houses one long folded sheet, an accordion of pictures, pasted-in letters, hand-scribbled and typewritten text. This unexpected book-form embodies a different kind of connectivity between the reader and what is written. With its layered folds the construction of the accordion suggests a different relationship between story and its experienced temporality. Before we’ve even read the first line, Carson forces us to sensually read and feel the text, to understand with fingers and eyes — we read without words. We must open the box, find its secret. Lift the heft of the zigzagging page, careful not to spill it. We do not merely start reading, but are offered an encounter. Photocopied pages from books and articles, well-worn and folded notes, dog-eared photographs and the visual echoes of writing (a pencil pressed into a page too hard) all lend themselves to the creation of authenticity, the personal, while also expressing the lack that inevitably surrounds these traces—these things only lead back, but do not (re)capture.

An academic and poet, Carson leans on poetry, history, and etymology to answer her questions and fill grief’s emptiness. Her questions range from the intimately personal (Who was my brother? To me?) to the generalizable or philosophical (How have people written of loss historically? How do the words and practices of the past shape who we are? How we grieve and how we feel?). She covers the gamut examining historical texts from the ancient Greeks to historical texts from her family’s archive. Placing these works side by side suggests their similarity as practices of collection, keeping, and knowing, that ultimately cannot offer enough truth or consolation in the face of a death’s void. Carson records her brother’s life (or more his death?) like a history or legend. She makes it akin to her precious academic artifacts perhaps hoping to rub more epic meaning on the ordinariness of her loss. Or, perhaps in this move, she stresses the power of context — the intimate experiences of “my life” are felt as mythic in proportion. She then invites us into this scrapbook of her personal tragedy — asks us to place it beside Oedipus and Antigone, Romeo, Hamlet.

Carson reminds us that our lives — even as we live them daily, solidly, in what we deem “reality” — are made up of things that are only close to us, or pretend to be us. We compose ourselves through the stories we remember, the stories we choose to tell and not tell, archives we endorse or simply leave behind. Carson tries to re-member her brother through or as an object — the writing, the book. He is brought together in pieces like Osiris, reformed, but the product is never satisfactory. Always product, never brother. A collection of scraps and fragments, this text, and perhaps all our histories, form poetic statements that yearn for context, detail and connection, but they also stand alone as particularly resonant poetic moments of open-endedness — fragments that can only create the feelings/meanings they create because of their inherent disconnection.

I can’t say that writing/building/making this text was a salve of some kind to its maker. I don’t know if it brought relief or consolation or even if consolation is at all ever possible. I can say however that the reading and experiencing of Carson’s Nox is the closest thing I’ve found to someone saying “I know how you feel. I’ve been there. I am there,” while also being the closest I’ve felt to actually believing that statement.

—

Ana Holguin writes PopHeart for The Idler.

Reblogged this on turbidus.

I appreciate your take on Anne Carson’s assemblage/elegy for all the resons you give in your post. So much more lasting than the bulk of memoirs on grief in the growing collection. Thanks.