Drawn out

If there were a single lesson to be learned from the collective knowledge unleashed at University of Chicago’s Comics: Philosophy and Practice conference, it would be that drawing is deeply democratic. To hear many of the 17 world-famous cartoonists in attendance tell it, no other action exists that retains as much validity without the burden of objective quality. This may be a difficult pill to swallow from a crowd that has defined the development and success of the graphic novel over the last 40 years. When you boil it down, though, the act of making a mark transports and transcends both experience and stature — subversively showing up in meeting-coma doodles as often as on the tightly constructed twelve panel page. At its core, the work of luminaries such as Robert and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Daniel Clowes, Lynda Barry or Ivan Brunetti represent the triumph of the doodle as much as that of the established page.

In particular, Kominsky and Brunetti have each created a character of their autobiographical selves that reflect and refract their personal experience as an artist. In contrast to the internal figure in solidarity, these self-portraits are the curse symbols (%$#!) to our everyday words, doodles of sorts that happen half on the page and half in your head. They exist to represent not simply that which is un-shown, but more so that which can be un-showable.

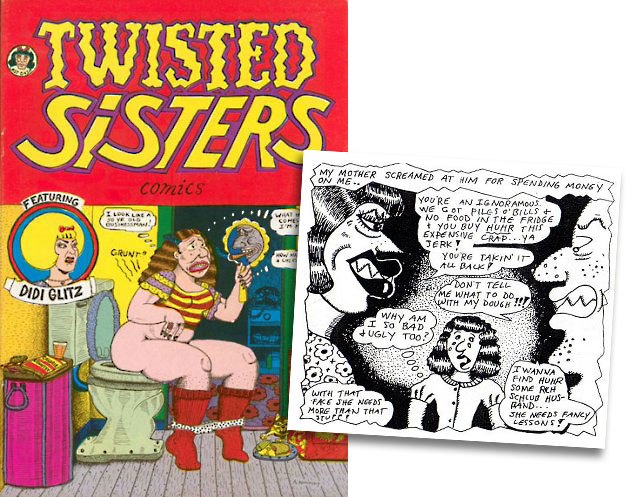

Aline Kominsky-Crumb began her career, years before appending her husband’s name to her own, as what many consider the first autobiographical female cartoonist. In the early 1970s, when women across the country were embracing feminism in personal as well as political life, Kominsky was scorned by her peers for pushing boundaries that seem somewhat unthinkable, perhaps even now. The art world too was growing aggressively anti-narrative with abstract expressionism replacing realism as a focus in the classroom. Amid rising social upheaval, Kominsky tells of a childhood distinctly defined by out-of-control middle class Jewish parents, whose greatest vision for their artsy and strange daughter was to become a cultivated product that could be sold to an orthodontist. Out of this set of conflicts grew her most famous self-caricature: The Bunch, an autobiographical doodle of sorts and one of many features in Twisted Sisters Comics.

The Bunch represents a side of the girl’s experience that still remains largely untold — a mix of complete disappointment with early sexual experience, curiosity about the world, simultaneously wanting to be an object of desire and acknowledging the reality of having a woman’s body. Frequently labeled an “Uncle Tom” for asking why attractiveness to men can’t also be about power, Kominsky took a step further and drew herself as a fully biological body. In fact, she went so far as to depict herself on the toilet for the cover of Twisted Sisters’ inaugural issue. As Kominsky put it so elegantly during her dialogue with University of Chicago’s Kristen Schilt, “That was a big no-no. A woman drawing herself and her bodily functions was considered completely unfeminine.” But when queried about the bravery involved in creating that sort of mark, Kominsky drew a blank. She’s never understood why more women don’t talk about or depict these sorts of things — it just seems obvious to her.

It isn’t just physical representation that makes the Bunch stand out among cartoon self-representations. While Kominsky describes her own artistic talent as limited by comparison to her peers, the truth is there’s a great skill in developing deliberate ugliness that transcends physicality. Yes, the Bunch starts with a large nose (and ends in a posterior drawn to knock over candelabras), but it’s the rage and humor that Kominsky packs onto the character that define her. The vision in the Bunch’s mirror is distorted not just as a reflection, but also as a culmination of a childhood spent lining teddy bears up along the wall to protect her at night. It’s both her warped sense of control and her sexuality: a made-up seduction in real life turned inside out, spilled ugly on the page. At its root, to draw out one’s own grotesque nature is a defense turned offense — empowerment through self-definition.

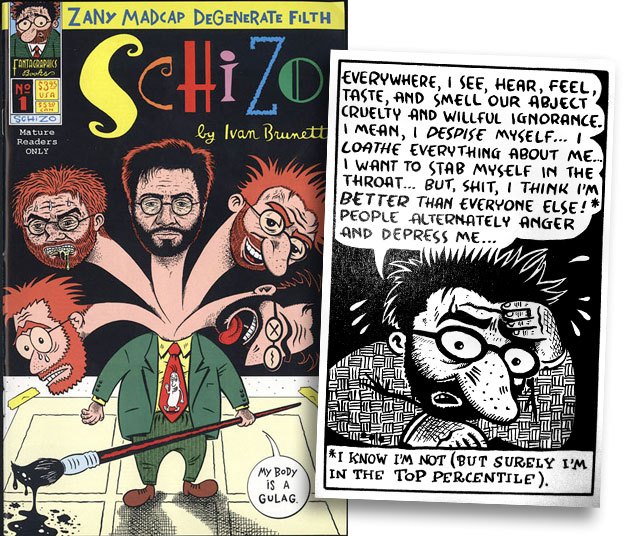

Likewise, Ivan Brunetti aggressively ponders his own grotesque interior/exterior in his 1995 Antarctic Press series Schizo Comics, collected in the single volume Misery Loves Comedy by Fantagraphic Books. In Brunetti’s self-caricatures, the compulsion to defend self-loathing through ever more graphic means creates a palpable discomfort only overwhelmed by my own anxious fascination. I simply can’t look away. His drawn body becomes the car crash, with every appendage, whisker, and nostril strewn across the page in a debauched panic.

In the span of four pages, Brunetti’s figure punches himself in the stomach repeatedly while uttering profanities; imagines himself melting in a Holocaust gas chamber; faces nuclear devastation; ages and decays to a skeleton; and is ultimately impaled, raped, shot in the head, beaten, urinated upon, beheaded, eaten alive, stabbed, and immolated — all by other versions of himself. The sheer volume of self- and other-focused destruction page after page could wear you down, but Brunetti smartly avoids tedium through constantly reinventing his own caricature. Like the five-headed hydra referenced on the cover of Schizo’s first issue, every version of himself destroyed is rejuvenated in a different style. Ranging from photo-realism and cubism to parodies of Charlie Brown and Dennis the Menace, Brunetti’s self-images shift and evolve in unexpected ways at each page turn, as if the ink itself was being reconfigured independently of the pen.

When asked what the most disgusting thing from his private sketchbook was, Brunetti confidently shared that his published material is far worse than any such unpublished. Truly, his work requires a strong stomach and just a little bit of sick humor, but that’s part of what makes it so compelling. Brunetti’s diseased body and mind are drawn together, entwined much the way art and text are on the comic page. The combination simultaneously creates an art form that elevates and mongrelizes their independent qualities. If words and pictures are rivals for our attention, Brunetti’s ugliness is the result of a drawn body assaulted by written thoughts, vice versa and in serial fashion.

So, to paraphrase Art Spiegelman’s keynote remarks, what the %$#! did happen to comics? Interestingly enough and much to my surprise at the time, the answer was, and was always meant to be, they got even better. The bodies and souls on Kominsky’s and Brunetti’s comic pages may be distorted and disfigured, but the vision of the graphic novel and cartooning in general couldn’t look more healthy. To spend a weekend listening to comic artists in dialogue, with each other and literary scholars, signifies much more than just an intellectual exercise. The comic itself has become an indelible mark on our culture, a transformative collaboration in its own right between word and picture, frame and content, body and thought. For if drawing is democratic, then the comic book is our new republic. We have all had a stake and an impact in its success.

—

Matt Santori-Griffith owns one business suit, three pairs of shoes, and over 15,000 comic books. He works a day job as an art director for several non-profit organizations, but spends his dark nights and weekends fighting the good fight on Twitter.com in the guise of @FotoCub. He has not yet saved the world, but isn’t giving up quite yet.

Comments

One Response to “Drawn out”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...[…] up in meeting-coma doodles as often as on the tightly constructed twelve panel page.” Read “Drawn out” by Matt […]